The Buddy System

The first step in creating CLDs: find a buddy, friend or coworker with whom to share the diagram. When I started working with CLDs, I didn’t pay attention to this. It’s come to my attention lately that I add something to every diagram that comes my way, and every diagram I send out comes back with meaningful corrections or contributions. This happens because everyone’s world view is slightly different. Most world views overlap enough that we can understand each other, but are different enough that other people will think of things you don’t. If you’d like, you can send me your drawings for review and comment.

If one is necessary, two may be better. At some point adding people will create more “drag” on progress than contributing “thrust” towards completeness. In a work environment completeness counts more than speed, so make sure all view points get considered. For independent work, I prefer “mostly complete” and quickness.

When sharing with your buddy, consider how you’re going to present the CLD. I worked with a friend on the phone on time and tried to draw the CLD as he described his drawing. Unless you enjoy lessons in miscommunication, skip this and at least send some sort of a drawing (JPEG, GIF, PNG) they can view, print and mark up. I’ve found sending the actual drawing works best. For Windows users, I typically use Visio. I have a template for CLDs using Jerry Weinberg’s notation that my friend Brian Pioreck created. When I’m working with Mac users, I use Canvas to create the CLDs. In both cases, we can change the CLD and share the results via email.

Creating a CLD usually follows these steps:

- Find some puzzling question.

- Think about the question.

- List some variables related to the question.

- Connect the variables showing how one influences others.

- Check the CLD by reading the story.

- Repeat steps 2 – 5 as necessary and appropriate.

What was that?

This question usually starts my systems thinking mode. I recently read an email by an author who stated “I never sign a contract for a book until the book is written.” Why not? What’s bad about some “up front cash”? What might be true for him to feel that way?

Thinking

Sometimes when I think, things instantly pop into my mind. Sometimes I commit the problem to my subconscious and do something else. I have favorite activities that involve my body, but leave my mind free (like bush hogging). Other activities (like Aikido, hitting golf balls) occupy all of me. In the contract situation, I received the email late in the evening. I fired off a “let me think about this” email and went to bed.

Thinking about question the hopefully leads to a deeper understanding of the situation. If it doesn’t perhaps the question is too small or too big. Perhaps the question isn’t clearly stated. Try changing the question and see how it changes your thinking.

As I thought about the question, I eventually centered on writing’s financial and personal affects.

Variables

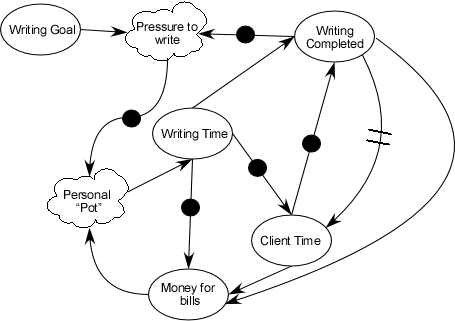

Now it’s time to list the variables you’ve discovered in your thinking. Choose things that can change. I use a laptop and word processor when I write. This doesn’t change, and doesn’t influence anything else. “Writing Time” changes and does influence other variables. I like to use variable names that work with “As ‘insert name’ goes up (or down), then ‘downstream name’ goes down (or up).” This verifies some constant doesn’t slip in, and starts the next step. For this example I chose the following variables:

- Writing Goal

- Pressure to write (added on second pass)

- Writing Completed

- Work Time

- Money for bills

- Writing Time

- Personal “pot” (how I feel about myself).

Getting all the variables in the first pass doesn’t happen often. The point here involves looking for hidden structures that create the observed dynamics. As the drawing takes shape, new variables appear, and old variables may not be needed. It depends on your point of view.

Which Comes First?

Since all the variables are related, and you can start reading a CLD at any point, it doesn’t matter which variable gets put in the drawing first. Pick one and get started telling the story. Once in a great while I do a hand sketch. Generally I head straight to the drawing package where I can cut, paste, drag and drop. When I finished, this is what my CLD for “Why not sign a publishing contract for an un-written book?” looks like:

And Back Through

As I draw the CLD, I find myself rethinking assumptions and conclusions. This restarts me iterating through the steps. Don’t be surprised if it takes several iterations to become comfortable witht the CLD. Eventually, I declare “Good enough” and quit.

The Never Ending Cycle

If you take the same variables and create a CLD you probably won’t get exactly the same drawing. That’s OK. I see where I can make a couple of changes. But at this time, this drawing closely represents what I think about the question.

Causal Loop Diagrams give us a method for revealing hidden system structure. Being able to read and create CLDs provides another path for sharing our current understanding.

Update 2010.1.28

I still create Diagram of Effects when I find sticky issues, those things that hang around, even when I try to fix them.

I now use Inkscape to create my diagrams. I have a template I’ll share if you ask. I still have the Visio template too.

Hi

Can you please share the Visio template with me.

Thanx

Olof

Hello Donald,

I recently found your site, it is a great inspiration and good help. CLD are, even I need to get used to them, a helpful tool to find out and especially to _explain_ why things probably happen.

Would you please be so kind and share your Visio template with me? Thanks a lot!

Regards

Marc