Googling “organizational change” returns almost 6 million hits. The LinkedIn Organizational Change Practitioners contains 26,125 members. With this much information and so many people practicing organizational change, you’d think we’d be good at it.

But that’s not what I usually experience in my work. Why does this gap exist?

A Handful of Change Models1

My recent posts have centered around the Satir Change Model. This describes how people respond to change. But how do we change organizations?

- The Diffusion Model, which says change more or less happens. A common example of this would be communities of practice in an organization. People choose to meet and share ideas and how they accomplish their tasks. Attendees can choose or adopt new ideas and practices, or not.

- The Hole-in-the-Floor Model, which says change is dropped on changes by planners upstairs. Process improvement committees and “You will now be Agile” mandates fall into this category.

- The Newtonian Model, which introduces the concept of external motivation to change. Often this takes the form of upper managers creating a sense of urgency, walking around with Gantt charts checking to make sure every thing’s reported on schedule, blaming resistors and beating up the laggards.

- The Learning Curve Model, which considers the time to adapt to something new. On the job training and mentoring fall into this category.

Other models exist, but often they fall into one of the above categories.

A Little More About Organizations

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary “an administrative and functional structure (as a business or a political party)” describes what I mean when I say “organization”.

This means we change an organization by re-arranging its structure. We add a new department (Quality Control), insert a new role (Director of Quality), reassign people, update the HR manuals, and re-draw the development process. Implement the new structure and we’re done! Sort of. If the change doesn’t seem to work fast enough, we can increase the pressure or put motivational posters on the wall.

But What About the People?

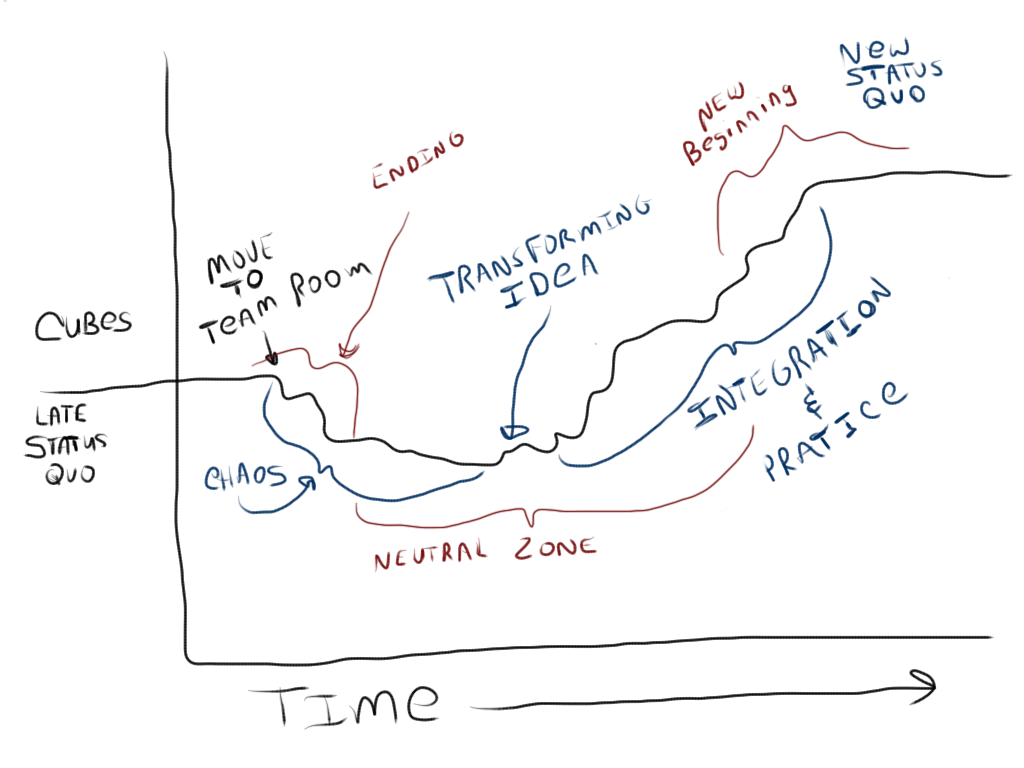

- Ending – Letting go of the old ways and the old identity people had. This first phase of transition is an ending, and the time when you need to help people to deal with their losses.

- Neutral Zone -Going to an in-between time when the old is gone, but the new isn’t fully operational. We call this time the “neutral zone”: it’s when critical psychological realignments and repatternings take place.

- New Beginning – Coming out of transition and making a new beginning. This is when people develop the new identity, experience the new energy, and discover the new sense of purpose that make the change begin to work.

Using our previous example of moving a cross functional development team into a team room:

Moving to the team room represents the change. Make the announcement and move. I’ve seen teams pick up their computers, manuals and move. I’ve worked where “facilities” moved the equipment and books over the weekend. Either move has a discrete start and end. The change announcement starts the transition process.

When team members hear they’re moving to a team room, they wonder: “What will it be like?”, “How will this affect my ability to concentrate?”, “If I play along, how long will it take before we move back into cubes?”

After the equipment arrives and they’re sitting in the team room, they start to adapt to their new surroundings. They may establish times when the team tries to stay quiet. Two or three may go to the whiteboard and have a conversation about a piece of code. They develop simple rules for handling interruptions.

Eventually the team room becomes the norm. Team members become comfortable with the change to the team room. I’ve seen those most opposed to moving become ardent supporters for the change.

Handy Reminders

Companies change.

People transition.

Not everyone in the organization completes the transition started by the change.

Those who do make the transition from ending to new beginning do so at different rates.

“You need all three phases, and in that order for a transition to work. The phases don’t happen separately; they often go on at the same time. Perhaps it would be more accurate to think of them as three processes and to say that the transition cannot be completed until all three of taken place.”2

You can help people understand and transition quicker. Bring in a change artist like me who has domain experience and has helped other organizations and their employees through the change/transition process.

1You can read more about these models in Quality Software Management Vol 4 Anticipating Change, © 1997 Gerald M. Weinberg, ISBN 0-932633-32-3 pp 3-14 If you prefer ebooks Becoming a Change Artist contains this material and more

2Managing Transitions, Making the Most of Change, ©2003 William Bridges and Associates, ISBN 978-0-7382-0824-4 page 9